“It was wrong what they did, and I will continue pushing them to see that what I am saying is right.”

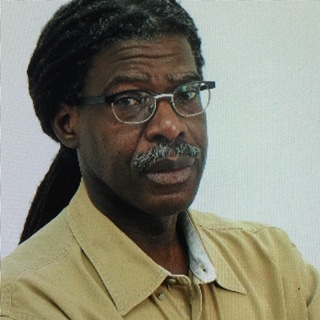

Andrew Harris, before his death in 2018, speaking about discrimination within the Worcester Police Department.

In 1997, Megan Boler, a researcher at the University of Toronto, published an abstract questioning the efficacy of the “passive empathy” often taught in schools.

“I am not convinced that empathy leads to anything close to justice, to any shift in existing power relations,” she wrote.

While Ms. Boler was specifically addressing social justice within the context of teaching and learning, her analysis is applicable to the wider society.

The common concept of putting oneself in the other person’s shoes, she explained, may not “radically challenge” one’s world view.”

“By imagining my own similar vulnerabilities, I claim ‘I know what you are feeling because I fear that could happen to me,” she wrote.

“The agent of empathy, then, is a fear for oneself. This signals the first risk of empathy: (It) is more a story and projection of myself than an understanding of you.”

Worcester’s residents need not be steeped in academic pedagogy to understand Ms. Boler’s reasoning.

The city professing empathy with its African American residents’ struggles while obstinately rejecting the truth of its racist past and present explains her theory well.

And perhaps, there is no better example of this unwillingness to acknowledge its past than the odyssey of a 26-years-old discrimination suit brought against the city two former black police officers, Spencer Tatum and Andrew Harris, who died in 2018.

The officers claimed they should have been promoted under a binding Equal Opportunity Action Agreement the city signed with the MCAD in 1988. The plan gave the city the flexibility to promote minority officers who passed the exams ahead of others who might have scored higher.

The MCAD agreed, and in 2011, the commission ruled in favor of the officers, citing the “substantial discriminatory impact of (the city’s) employment practices on minority officers” and ordering retroactive promotions and monetary damages to the officers.

However, the city chased every legal means to deny the officers their promotion and retroactive pay, appealing the 2011 ruling, and repealing again when the MCAD affirmed the ruling in 2015.

On Jan. 6, the Worcester Superior Court upheld the MCAD’s 2015 affirmation. According to the officers’ lawyer Harold Lichten, the case’s drawn-out nature could cost the city $6.5 million.

But it wouldn’t surprise me if the city appeals again.

As usual, the city will claim things are not what they used to be back when the officers first brought the suit.

There is some truth to that.

But as Mr. Harris said just prior to his death, the changes are merely defensive maneuvers.

“If Spencer and I didn’t bring this case, they would have stuck with everything they had done in the past,” he said then.

“It was wrong what they did, and I will continue pushing them to see that what I am saying is right.”

I’m not sure if the city will ever admit to its wrongs.

But I bet it will continue to settle police brutality cases without admitting guilt.

And it will continue to honor Martin Luther King one day a year and spend the remainder acting contrary to his teachings.

That is the passive empathy of which Ms. Boler speaks.