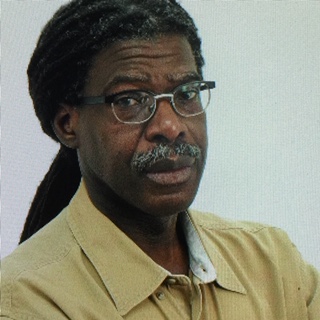

City Councilor Sean Rose not black enough, a community member says.

Recently, a “prominent” member of the black community dissed City Councilor Sean Rose by claiming that his colleague Khrystian King was the city’s only black councilor.

Mr. Rose wouldn’t name the community member.

But the assertion is another way of saying he “isn’t black enough,” which in the black community carries the same searing dismissal of one’s sense of self as being called the “N” word by a white person.

Yet this broadside against Mr. Rose “sadly” went unchallenged. It also wasn’t the first time his blackness was questioned, he noted in a Facebook post.

“Over the last couple of months, I’ve been told and have heard the following: Is Sean Rose black? Where are Sean Roses’ black friends? Are you black, though?” he wrote.

Questioning Mr. Rose’s blackness is one of the many destructive offshoots of slavery that still flourishes within the black community.

Malcolm X famously drew attention to it in his parable of the “House Negro.”

“…There were two kinds of slaves, the house Negro and the field Negro,” he said at Detroit’s King Solomon Baptist Church in 1963.

“The house Negroes–they lived in the house with master, they dressed pretty good, they ate good because they ate his food–what he left.

“They lived in the attic or the basement, but still they lived near their master; and they loved their master more than their master loved himself.

“They would give their life to save their master’s house–quicker than the master would.”

The modern house negro, Malcolm said, “Loves his master. He wants to live near him. He’ll pay three times as much as the house is worth just to live near his master, and then brag about ‘I’m the only Negro out here.’

“‘I’m the only one on my job. I’m the only one in this school.’ You’re nothing but a house Negro.”

Today, the “House Negro” taint is more broadly applied. A person’s skin tone, her profession, her politics and her social group can raise questions about her “blackness.”

The sports she plays, the high school classes in which she enrolls, and even the clothes she wears are fair game for the House Negro taint throwers.

Now, I can understand people’s frustration with blacks like Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson, both of whom go to great extremes in denying the corrosive legacy of slavery.

But you don’t dismiss them by denying their blackness. See them as proof that black people, like everyone else, are susceptible to fallacious reasoning, selfishness, greed and indifference.

One of my biracial daughters used to raise the “not black enough” issue with me during her high school years.

“A lot of it was ‘Oh, you are lighter skin, therefore you don’t experience the same things I experience being black,’” she recalled recently.

“That I can understand. I’m black, but that doesn’t mean I experience the same world as darker-skinned black people do. Being light-skinned, I know I do have privileges that they don’t.

“But a lot of the times, it was also, ‘Oh, you are not really black’ and I felt I had to understand where they were coming from. Why were they saying that?

“Then, I stopped defending myself because I know who I am.”

My daughter’s compassionate stance is reflective of the younger generation’s true social justice instinct, a reason perhaps for us to remain hopeful that, even with this hiccup in presidential leadership, the country will ultimately hew to its better self.

I, on the other hand, believe this “not black enough” taint is dangerous and sprouts from the same bed as every other form of dehumanizing instinct.

In general, it presupposes that the blackness of one’s skin is a necessary determinant in understanding inequality, injustice and privilege; or that being black is a uniform way of thinking; or that one’s life experiences or one’s social circle determines one’s blackness.

Mr. Rose’s legitimacy as a black person seems to be in question on all those fronts–the lightness of his Cape Verdean skin, his politics and his social circle.

In his Facebook post, Mr. Rose noted that, like many African Americans, he faced “systemic racism, prejudice, bias and conditioning.”

Yet, it is not the color of Mr. Rose’s skin, his life experiences, his way of thinking, or his social circle that matters. What matters is his capacity to understand, to empathize and to change in ways that bend the arc of justice.

Councilor Rose’s decision to support a body camera program, but not the “defunding” of the of the police department should be judged on merit.

If you are so inclined, you may say his call for body cameras is too little too late. You could say that he is naive to think the city will ever adopt such a program.

But it is counterproductive and dangerous to suggest that the legislative path he chose means he is not black enough.

I’ll be the first to say that Mr. Rose and Mr. King have not done everything they can do to make the city more accountable to its black and brown communities.

And I will always call them out in hopes of getting them to do more.

What I won’t do is question the purity of their racial identity. That’s a Trumpian move, and we know where that leads.

Feel free to share your opinion on this issue in the comment section.